Transforming energy codes to transform façades

Compliance with mandatory energy codes in the United States, with some important exceptions, typically does not result in high-performance installed fenestration and façades. This is because of:

- The way codes are written, adopted and enforced.

- The absence of an envelope-first approach in any of the U.S. model codes.

This blog focuses on strategies to remove the first set of structural barriers. I will address the second next month.

Code Structural Challenges

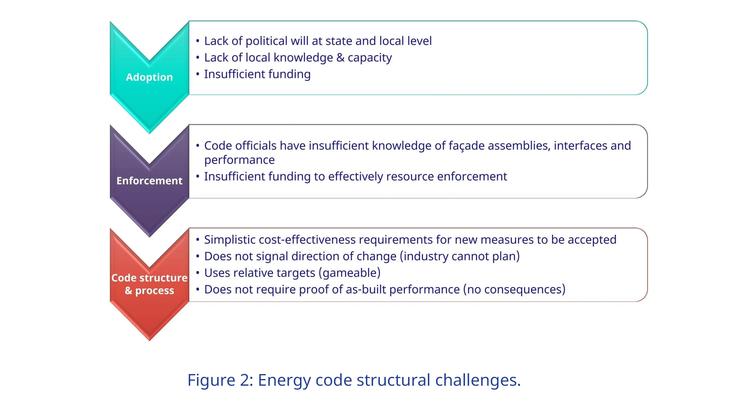

The structural challenges due to the way codes are written, adopted and enforced are numerous (see the Façade Tectonics Institute’s (FTI) report on barriers to adoption of high-performance façades, authored by Steve Selkowitz and me, for more details):

- Insufficient knowledge and resources are available at the state and local level to support model code adoption (and any jurisdiction-specific modifications) and adequate enforcement.

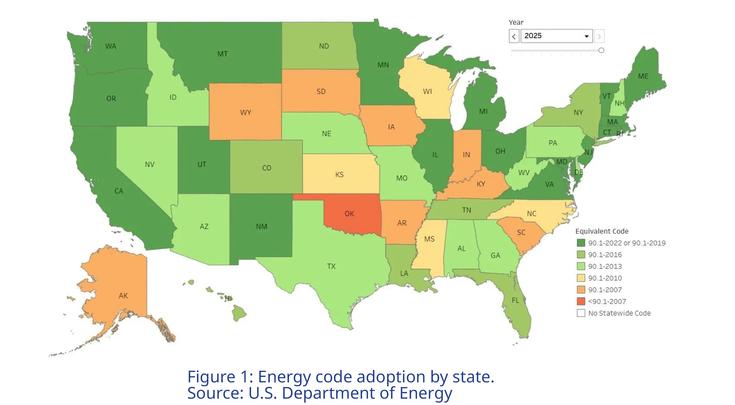

- Lack of political will at the state level to adopt the latest model codes. This, and the lack of investment in resources, are key reasons that the U.S. is a patchwork of model code adoption (see figure 1). Some states have codes worse than the 2007 version of the model code, whereas a few have already adopted the most recent version.

- Simplistic cost-effectiveness requirements for code changes are based on energy cost savings only and do not consider upfront cost reduction from reducing internal systems, nor the impact of carbon-emission reductions, improved resilience or any other occupant health-related benefits from the provision of comfortable daylight and views.

- Codes do not signal the direction of change, so capacity cannot be built up in the market to support future needs and improve cost-effectiveness.

- Codes use relative targets for building performance. This leads to simulators making the reference building perform as poorly as possible to make the proposed building comply.

- Codes typically do not require proof of as-built performance. The certificate of occupancy, that is, sign-off by the code official, is given before the energy performance of the building can be assessed.

Addressing Model Code Structural Challenges

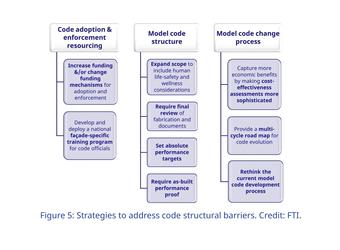

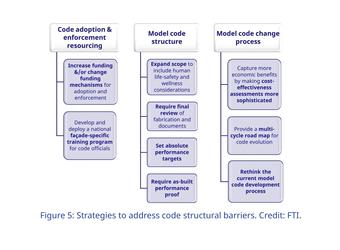

The following is a set of ideas to address these structural challenges collated by the FTI research:

- Increase funding to code offices for code development, adoption and enforcement. Seattle offers a model for how to appropriately fund a code office that has the capacity to both develop and analyze new code proposals and to enforce envelope-specific requirements. Unlike most code offices, which are insufficiently funded from building permit revenue, Seattle’s energy code enforcement and development is well-funded by the local utility, which views it as an investment in energy efficiency.

- Seattle’s code office has the capacity to develop new codes: Seattle’s energy is always a step ahead of Washington State, which is an early adopter of the newest model codes. And Seattle plays an active role in the national model code development, with energy code advisor, Duane Jonlin, chairing the 2024 and 2027 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) consensus committees. The number of personnel, their qualifications and investments in training enable them to understand the façade details they are reviewing for compliance. Code enforcement is tight in Seattle.

- The North East Energy Efficiency Partnership (NEEP) recommends providing economic incentives to states and local jurisdictions for new model code implementation and enforcement. Funding for such was included in the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. NEEP also recommends diversifying state-level stakeholder engagement and outreach during the model code-adoption process, and developing and funding education.

- Require final fabrication and document reviews for code compliance: Requiring drawing reviews and delivery of testing reports, commissioning data and proof of fenestration performance through National Fenestration Rating Council (NFRC) label certificates to the code official to validate what is being constructed could be impactful. New York City requires that final fabrication drawings for fenestration and opaque assemblies be submitted for final code review. California and Seattle have strict requirements for submission of NFRC label certificates for commercial fenestration. Few others do.

- A national training program for code officials focused on façade-related code compliance. To be able to enforce and develop codes, sufficient well-trained staff is critical. Such training would include the identification of thermal bridges on plan documents and the assessment of fenestration and opaque assembly thermal performance.

- Make cost-effectiveness requirements more sophisticated to capture more than energy cost savings. Massachusetts has addressed this problem by engaging consultants and a general contractor to simulate and price the holistic impact of envelope performance improvements, including a reduction in HVAC capacity. The result: A widely adopted stretch energy code that has resulted in a step change in installed façade performance and is recognized as the most stringent energy code in the country.

- Because of its mandate to achieve carbon reduction goals, Washington State requires that a new measure be shown to be the most cost-effective available means of attaining the needed improvement in energy performance, rather than imposing a specific cost-effectiveness requirement.

- Using the social cost of carbon (SCC) emissions to assess payback would also support implementing more stringent envelope performance. As an aside, we are currently witnessing the SCC through the impact of climate change on the rapid rise in our home insurance policies, especially those located in hurricane- and fire-prone regions. The International Code Council developed a method for assessing payback on SCC for the 2024 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC). However, it was for informational purposes only and could not be used to justify code changes.

- Considering the payback on life-safety from improved passive survivability would also support better façade performance.

- Rethink energy code scope: As energy performance requirements increase, there is a tension between transparent and opaque areas on the façade. This is because the lowest cost route to achieving the needed performance is often to increase the opaque coverage. Broadening the scope, especially to address the human need for daylight and views, would help avoid this potential unintended consequence of a singular focus on energy.

- Last month, the first step was taken. Subject to final public review, the scope of the 2027 International Building Code will be expanded to include a requirement for a minimum amount of glazing in classrooms and all Group R occupancies, and living and sleeping spaces. Kudos to the National Glass Association’s team (Tom Culp, Urmilla Sowell and Thom Zaremba) for supporting these proposals over several years. Having a backstop for transparency is critical.

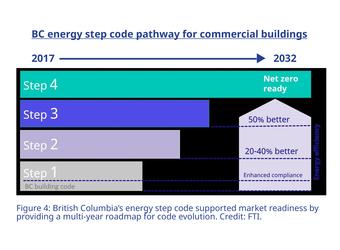

- Create a code evolution roadmap to give the market predictability, confidence to make needed investments in new products and capabilities, and a runway to get to higher performance. British Columbia has created an energy step code in which stepped increases in stringency are laid out with a multi-year implementation timetable to eventually get to net-zero performance.

- Change to absolute performance targets, such as energy use intensity (EUI), instead of relative performance to a variable (gameable) baseline, as British Columbia and Massachusetts have done.

- Require performance proof: Drive the use of building performance standards (BPS). While code compliance needs to be determined before the certificate of occupancy, if BPS is also implemented, newly constructed buildings would need to meet the annual BPS energy targets after a year of occupancy.

- Rethink the code development process: The FTI report suggested that the current model code development processes may not be capable of implementing many of the code structure-related concepts above in a timely manner. The reasons relate to the independence of the code development organizations and the strong influence of industry special interests. As an example of the headwinds, it cited the 2024-IECC appeals process in which special interest groups successfully overturned decarbonization provisions.

Many different changes are necessary to increase the minimum code requirements for façades across the entire U.S.

Providing funding and training programs for state and local code offices and funding for BPS implementation may turn out to be the easiest of the strategies to implement. Creating the political will for higher energy performance more uniformly across the country is likely the hardest challenge. However, broadening the conversation from just energy to thermal resilience and the ability to save lives in extreme weather may influence more political constituents.

A similar magnitude challenge is adapting the code development process to support the transformation of the code structure. An analysis of the capability of our current code development process in meeting future needs is highly recommended.

What got us here may not get us there.