Envelope-First Design: The Missing Link in US Model Building Energy Codes

A blog on usglassmag.com by Helen Sanders

The absence of an envelope-first approach in the United States model energy codes is a major reason why the construction of high-performance façades and the use of high-performance fenestration are not widespread. While new buildings built to more recent model codes may have an expectation of reasonable energy performance, their performance often derives from highly efficient and oversized HVAC systems, which compensate for a poor envelope.

Professor Ted Kesik, University of Toronto, likens these designs to a Major League Baseball pitcher with one freakishly muscular throwing arm and the rest of the body just flab.

When the power goes out during a winter or summer storm, the weakness of a poor envelope is discovered: The envelope is not good enough to maintain a life-sustaining indoor environment for humans. Likewise, during normal operation, the occupants sitting near the façade are often too hot or too cold or deal with sunlight glare during certain times of the day.

What is Envelope-First Design?

An envelope-first approach–sometimes called “fabric-first”–focuses on reducing heating, cooling and lighting loads caused by the envelope before addressing mechanical requirements.

PAE Engineers takes a unique load reduction approach to their building designs. For the net-zero energy, Living Building Challenge (LBC)-certified, Rocky Mountain Institute Innovation Center in Colorado, the firm first simulated a code-compliant envelope with no HVAC system. It calculated the minimum and maximum room temperature at the expected winter and summer external extremes. The team then made improvements to the envelope performance in the model until the minimum and maximum internal temperatures of 50 degrees Fahrenheit and 83 degrees Fahrenheit were achieved. These are high and low temperature limits for human survival.

Because of the extremes of the Colorado climate, R12 quad-pane fenestration with R50 walls and roof was required, along with low air-leakage and thermal bridge mitigation. Fenestration selection and façade positioning also supported passive solar heating and natural ventilation.

Only then was the HVAC system designed. According to Paul Schwer, president emeritus at PAE, the entire heating system uses the equivalent of 15 hair dryers of power, consisting of electric heating under the carpet and a heat recovery unit. It rarely needs to operate because of the high-performance façade.

The approach works in all climates. In more temperate climates, Schwer notes that just double-pane glazing is needed. This is exemplified by their LBC-certified, developer-led office building in Portland, Oregon (figure 2).

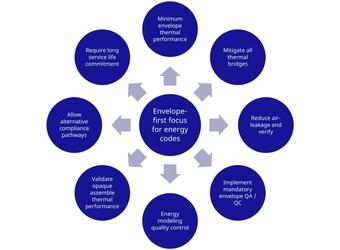

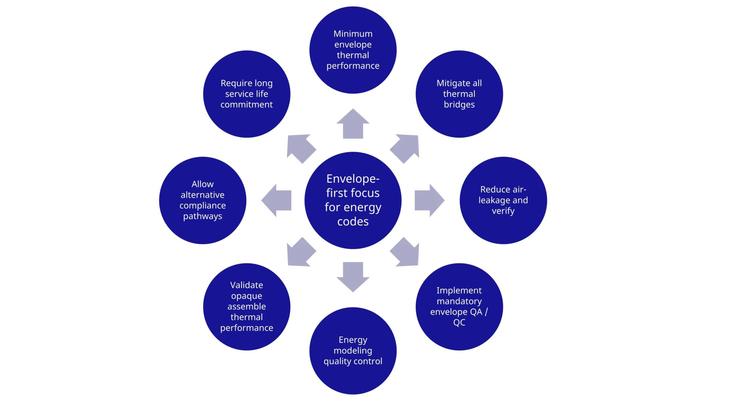

What is an Envelope-First Code?

Envelope-first codes prioritize envelope performance. They limit the ability of design teams to trade off increases in internal HVAC and lighting system efficiencies with degradations in performance of the façade. They also focus on verification of envelope installation quality, performance and durability.

Some leading jurisdictions, such as Massachusetts, British Columbia and the City of Seattle, have adopted codes with an envelope-first focus.

The following concepts for envelope-first code approaches were identified by the Façade Tectonics Institute’s blueprint for change in its 2024 market barriers report for the U.S. Department of Energy. Many have been adopted already by these leading jurisdictions.

- Require a minimum façade thermal performance through setting targets for an envelope-specific metric, like area-weighted U-factor (City of Seattle and Washington State) or Thermal Energy Demand Intensity (TEDI) for heating and cooling (Massachusetts, British Columbia). Do not allow envelope performance to be traded off with internal system efficiencies. Requirements to address overheating are also critical.

- Mitigate and account for thermal bridges: Implement requirements for identifying, more stringent mitigation, using performance de-rating in simulations and reporting thermal bridges on submittals. While the most recent model codes have begun to recognize and mitigate thermal bridging, there is a lot of room for improvement to match the requirements of Massachusetts and British Columbia.

- Reduce air leakage: Lower allowable air leakage and increase mandatory requirements for validation and testing across more buildings and climate zones. Air leakage is one of the largest degraders of energy performance and is an issue across all climates.

- Implement quality assurance and control (QA/QC), and envelope commissioning requirements: QA/QC for managing air-leakage, thermal bridging, water tightness, and continuity of insulation is critical during construction.

- Improve simulation quality to improve performance path compliance: Have QA/QC and standardization by requiring a standard simulation procedure (like in British Columbia) and for code compliance simulations to be completed by certified simulators.

- Require opaque assembly thermal performance validation: Unlike fenestration assemblies, opaque wall assemblies do not have a standard performance labeling and certification process. Significant thermal losses can occur because of thermal bridging due to the panel attachment means. Spandrel panel performance is also routinely overestimated and needs more accurate simulation methods.

- Allow alternative compliance pathways that have an envelope-first approach, such as passive house certifications from PHI and Phius. Removing the requirement to develop two separate energy models (one for passive house certification and one to demonstrate code compliance) reduces cost, complexity and conflicting requirements, and delivers higher-than-code envelope performance. Massachusetts and Denver allow passive house certification as an alternative compliance path for residential and nonresidential buildings.

- Require a long building service life commitment: This will naturally drive improvements in the quality of the façade as it is a driver of service life, especially water management. Designs will need to demonstrate that the façade is built to last from durable assemblies, with attention to water and dew-point management, and with quality installation.

An envelope-first approach is the missing link for improving the built outcomes from U.S. model energy codes. Several jurisdictions have provided models that move toward an envelope-first focus. The envelope-first measures listed above are gathered from those jurisdictions and façade design and construction best practices, and provide a blueprint for model code change.

I encourage our industry to actively support envelope-first code changes as they result in greater demand for high-performance fenestration and glazing products and high-quality installation services. Envelope-first codes also provide our industry with a seat at the design table from which we can influence design and construction. This can only be positive for industry growth and prosperity.